Soo… End-to-end encryption isn’t having the best of times. It does make it harder for state’s to spy on people which I guess is a ball-ache. Thus a tradeoff it presented: let’s throw cyber-security for law abiding citizens under a bus and in exchange make it more straight forward for law enforcement to target criminals. That’s not a great tradeoff but as much as I’d like to believe that’s the truth, I think even this sub-standard tradeoff is chimerical. I think what is really on the table here is throwing cyber-security for law abiding citizens under a bus and in exchange we make end-to-end encryption less convenient for criminals. And that’s an even worse tradeoff.

I figured this would be an interesting thing to implement – as a proof-of-concept – to see if it end-to-end encryption can be used in a self-hosting system. Now the elephant in the room is S/MIME (or PGP) but that’s awful. We will soon see that I have a very strong stomach for downright obtuse interfaces so if I say S/MIME sucks, that’s pretty damning. So we’re going to try to implement something more user-friendly than that, which isn’t too hard to accomplish.

Server-side

What we have is a GPG-based client and we’re also using GPG on the server end to implement certain operations while the majority of communications are authenticated with symmetric encryption. Creating organizations requires that you provide OpenPGP-signatures that correspond to these super-admins.

@app.route("/<organization_id>", methods=["GET", "POST"])GET is allowed for users of that organization. Creating users or modifying them require GPG signatures that match what the server recognizes to be administrators in the user’s organization.

@app.route("/<organization_id>/<user_id>", methods=["GET", "POST", "PUT"])A user can make a GET request of their own data but only admins can perform POST and PUT.

@app.route("/<organization_id>/<user_id>/password", methods=["GET"])The last use of GPG-signatures is when asking for a shared key for the server and the client to use for 24 hours to use symmetric encryption. There the client needs to sign a nonce and if this can be verified by the server the server responds with a shared key encrypted with the user’s public key.

fingerprint = backend.get_fingerprint(organization_id, user_id)

encrypted_key = crypto.encrypt_data(shared_key, fingerprint)So we have sort of double verification for establishing a mapping from user to shared key.

Asking if there are any new messages or sending one:

@app.route("/<organization_id>/<user_id>/message", methods=["GET", "POST"])Alongside getting the contents of a message and acknowledging the reception of a message:

@app.route("/<organization_id>/<user_id>/message/<message_id>", methods=["GET", "PUT"])All use symmetric encryption to generate an HMAC. It’s checked like so:

decoded_signature = utils.decode_data(encoded_signature)

shared_key = valkey_connection.get(f"shared_key_{organization_id}_{user_id}")

verified = crypto.verify_hmac(shared_key=shared_key,data=str(nonce),signature=decoded_signature)Before this we check for nonces being monotonically increasing which is a requirement. Consider if the communication happens in clear-text or you use Cloudflare or something and don’t trust that provider. The worst thing they can do is retransmit an HTTP-request and this doesn’t work so well because the nonce used for each request has to be monotonically increasing. So a request with a duplicate nonce isn’t valid even if the request has a correct signature.

What then if we both have a failure of the TLS/tunneling process and the nonce-memory server-side fails? Then a retransmission is possible! But the most you can learn from that is what someone’s encrypted message is, which isn’t very helpful. Also, that is what you can get from just the TLS failure. This is part of why the server isn’t something that needs trusting. It only ever stores UUIDs and various OpenPGP blobs, like signatures, keys and encrypted blobs.

So while TLS and a requirement for nonces to be monotonically increasing leaves an adversary trying to do mischief with a very narrow opening, even if those protections happen to fail in a way that lines up for a hacker, they could at most get their hands on the encrypted contents of a single messages or ask that idempotent operations be performed again.

Finally we check if nonces refer to a time at most 30 seconds ahead or 30 seconds behind what the server considers to be “now”. A window for malicious actions is very narrow and require multiple failures to line up in just the right way, and it gains you nothing.

Note: I don’t like making user interfaces and I’m bad at it – which is kind of a fortunate confluence of events – and that leaves us with no user interface for me to show. However, I argue that an interface would be stringent about anything coming from the server. Basically all users and keys are stored locally and any change proposed by the server is checked against existing keys. So even if someone gets control over a server and they try to change a bunch of keys for various users… they would get nowhere as all clients would balk at the notion of changes being performed without signatures matching the real – and previously established – administrators.

Oh, one thing I did check in terms of client software is that we can use Yubikeys just fine with this setup. Python-code has no idea how GPG handles signing and decrypting and using GPG already set up to use a Yubikey for OpenPGP operations worked just fine, it was plug-n’-play.

Two-man rule

This system implements a variant of the two-man rule. It’s basically a rule to prevent people from using nuclear warheads wrong, which is a reasonable things to want to prevent. A single person is hard to trust but two people? Everything from mental illness to substance abuse to corruption becomes less of a danger when the two people are involved. What use is there to one guard being suicidal and the other intent on stealing the warhead? You would need two people swayed and in the same way. It’s not perfect but the requirement to have at least two people around a nuclear warhead is an improvement.

There are two super-admins defined and both need to sign a organization id to create a new organization. An organization is created with just one admin so the code for perform “regular admin actions” looks like this:

admin_count = backend.get_admin_count(organization_id)

if (admin_count == 1 and good_signatures == 1) or (

admin_count > 1 and good_signatures > 1

):

<code for making the requested change>I could write that more concisely(probably?) but I find value in the logic being overt.

Scaling(1)

So what is the capacity of a self-hosted end-to-end encryption system? I am currently running the server-side stuff on a single node with 2 cores and 8 GB’s of RAM. We have unicorn with 4 workers running the business logic and an instance of Valkey as a caching layer and a MariaDB instance for persistence. That is currently yielding about 50 new messages per second and a similar number of checks for if there are new messages for a user, each second. So that’s going to serve organizations up to maybe a hundred users counting conservatively.

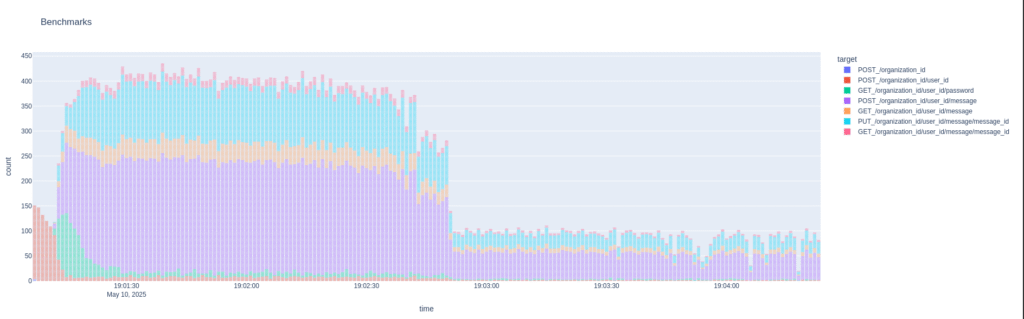

We max out at almost 250 operations per second but this puts heavy load on the node and isn’t steady-state.

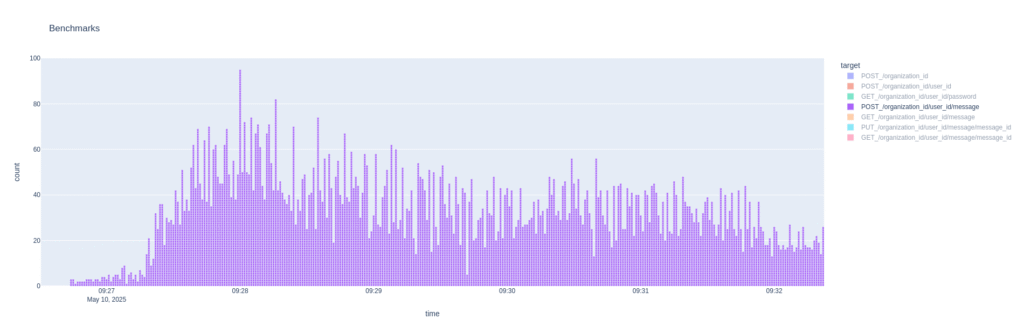

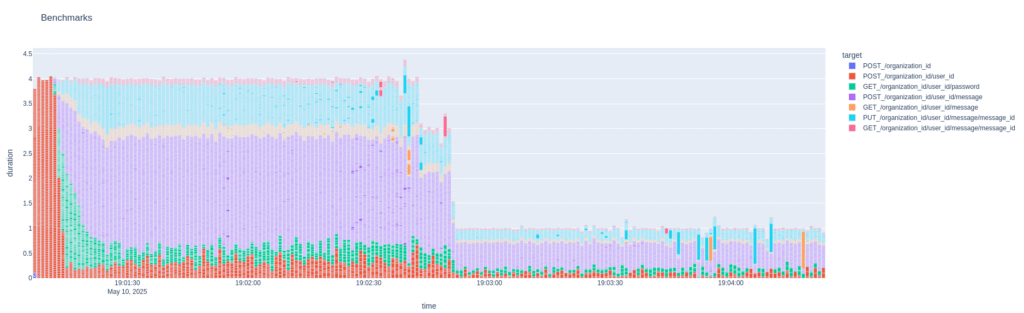

We can see that POSTs of new messages took quite a lot of time when seeing this burst in the beginning. (With multiple concurrent processes sending traffic more than 1 second of duration per second isn’t weird)

The long tail is just because one of the replayed logs is sending more than 10 000 messages in total, so it takes a while. This however doesn’t even make the VirtualBox VM from which i run these tests sweat even though it’s three processes in parallel making requests against the server.

This is good(and lead me to declare myself a legend) because I want to be able to test scaling this up further. A single node deployment is just a benchmark to compare other deployments to. If this was production stuff it would make sense to just add more CPUs and RAM to the one node rather than scale out but where’s the fun in that?

Scaling(2)

Oh, why use Valkey? It’s not so much to leverage the fast access times as it’s about reducing the traffic that goes to the persistence layer. Ephemeral chunks of data don’t need to be stored persistently so… let’s not.

Next we’ll try having gunicorn on a business-logic node by itself and let MariaDB and Valkey run on a separate node. We ought to incur some penalties by having traffic go over the network but we will have twice as many cores and twice as much RAM. Oh, I should probably get Grafana running so I can monitor these nodes to visualize the load. Me running top in the terminal isn’t conducive to me showing the load and CPU usage.

[Several hours later, only some of which was spent on this stuff]

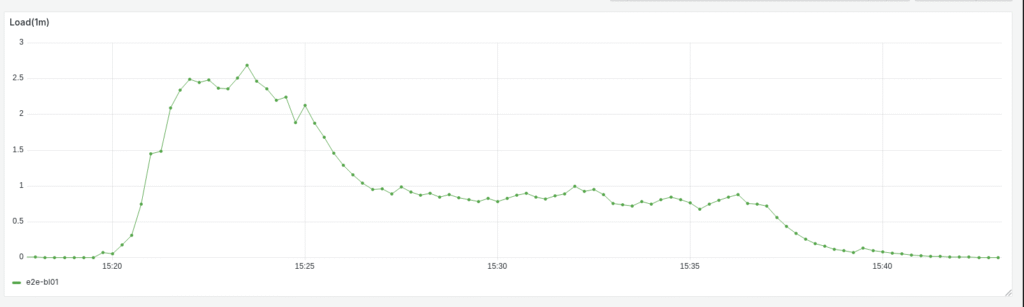

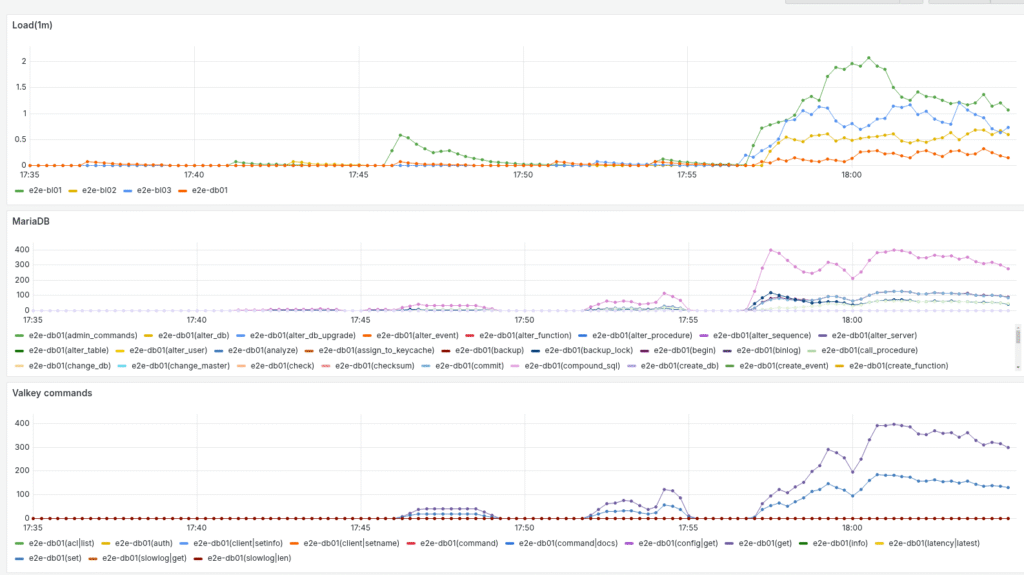

There, now Prometheus and Grafana is ready and we can show load:

Now, this is without an indices so I’ll run this again with those in place. Okey, this is weird. So I defined some indices in the code and… it worked. When you write SQL you need to expect that a few passes are necessary to make everything fall into place. I had to run “SHOW INDEX FOR messages;” to see if they were actually there are it seems like they are. Weird…

Well, anyway: the load goes up to 1.6 it seems now with the indices in place. I had expected a bigger change given the introduction of indices. I had better run slow query log. No, seems fine. I checked by issuing a query that I knew couldn’t use any index and it showed up in the slow query log with SET GLOBAL log_queries_not_using_indexes=ON;

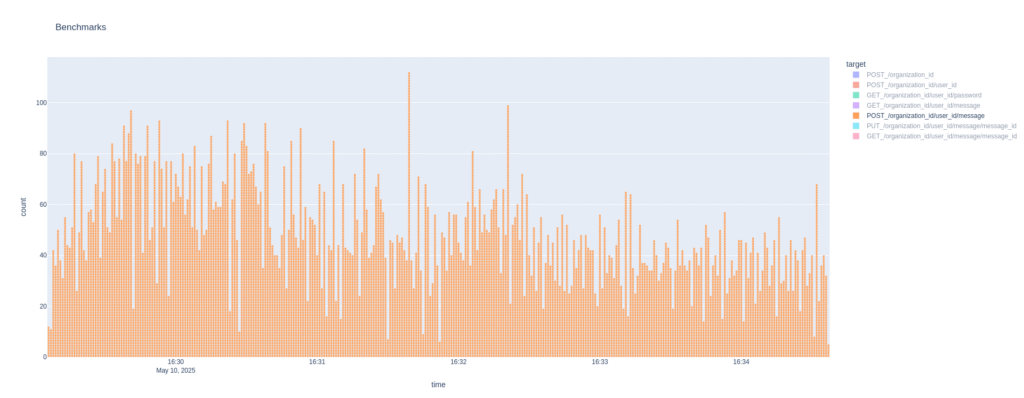

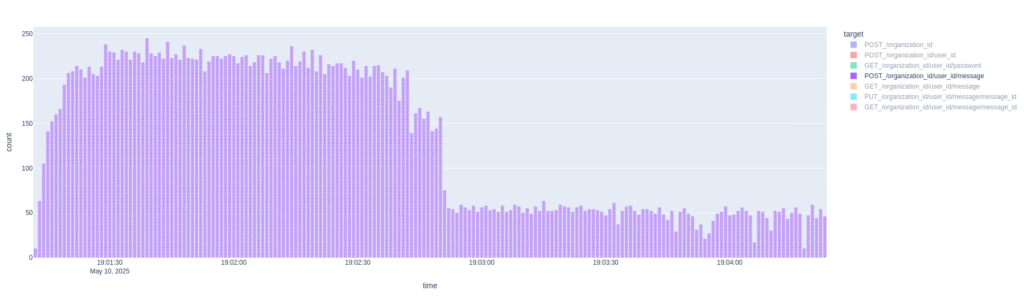

Anyway, let’s look at the throughput. Oh, wow. So that boosted throughput a bit:

Most notably it’s significantly shorter than before. As predicted this is fairly clear when looking at POST message:

Okey then, I’ll use the version with indices when I proceed. So it’s the business logic that needs the most resources. I’ll create two more business logic nodes to see if that is enough to saturate the database node, but I suspect I need to increase the amount of traffic from the client side to reach that goal.

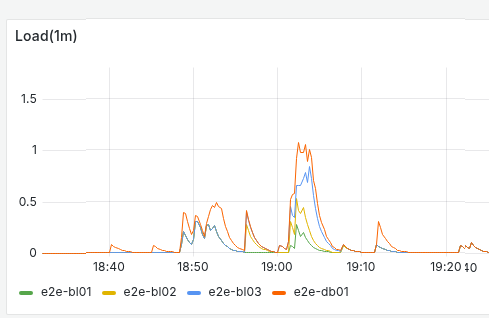

Yeah, I need to generate more traffic because the database node isn’t struggling with four independent streams.

This is with the lines stacked so the total load against three business logic nodes and a database node is just 1. And the total amount of traffic is substantial:

And new messages are processed at a rate of more than 200 per second.

Let’s see what the duration is.

Yeah, pretty clear how we’re limited by the clients not having time to send more traffic. I hope to be able to avoid making the dumb client asynchronous because I’m not overly familiar with async in Python, or any language really. No… I think I’ll try removing the indices to see if that allows me to put more strain on MariaDB because even with like 8 processes sending traffic and the business logic nodes struggling the database node isn’t even approaching a load of 1.

No more indices

Ah, yes, now the persistence node is considerably more strained so I can now have two more persistence nodes that are read-only replicas of the primary MariaDB host.

I went ahead and made an async dumb client. I got quite a bunch of failures before saying that the script shouldn’t pipeline the first few dozen requests or the client will fail to add initial users and then everything else fails as a consequence. Still not a lot of load on the database with the indices back in place(I did that during debugging the asynchronous client) so I’ll try remove one of two and see if I can get a reasonable database-load. I may have have screwed myself somewhat with using Valkey as it sees approximately the same number of operations per second as MariaDB. So I could have seen double the load on the MariaDB-node even with indices in place. Oh well.

Seems I have an issue with the client side records that I use to collate operations. I’ll see after the next simulation run is over. The logs are written at the end.

Backends

I argue that the business logic is already horizontally scalable. It’s not that we can’t cause issues by issuing 3 000 operations to 30 different business logic nodes that all try to get a shared password for one user. Well in reality the monotonically increasing nonce requirement will make that fall at the second hurdle, but my point is that the business logic scaling out horizontally can be undermined by crafting traffic carefully using credentials that allow you to perform operations in the system, but that’s not really what we’re trying to avoid. We could add rate-limiting for IP-addresses and have various guards in place to keep bots from causing issues if that was our concern.

But if we try to scale out MariaDB to 30 nodes that’s not going to work even with us trying to give that setup the best possible chances of success. MariaDB is a traditional RDBMS, it’s only going to handle a single primary and a small number of pure read replicas. So as it stands MariaDB is the bottleneck that puts an upper limit on how much traffic a cluster can handle. Sure, most work is done by the business logic and that scales quite well horizontally but eventually MariaDB will set the upper limit.

So I intend to implement a ScyllaDB backend and maybe even a pure Valkey backend. The former isn’t too hard, I made an early development version with Amazon Web Services DynamoDB as a backend. A pure Valkey backend is harder because even though ScyllaDB is a key-value database with lots of restrictions compared to an RDBMS like MariaDB, Valkey is pure a key-value store. Valkey expects one key and will give you one value. That value can be a list or an object attribute(called hashes in Valkey) but you can see the limitation I think.

But I have to get the asynchronous benchmarking software to work more correctly for it to be feasible for me to continue that process.

Partial conclusions

I argue that while this implementation is kind of crap and under no circumstances should be used for production deployments, the idea of having

- end-to-end encrypted communication

- a client running on an actual computer

- a Yubikey to hold your private key very safe

translates to something a lot of more secure than running WhatsApp on your smartphone. I’m not throwing shade on WhatsApp, but Samsung controls what runs on my smartphone and I wouldn’t trust them to handle sensitive data. With data exchanged using end-to-end encryption, a signature on a piece of paper won’t do much to help law enforcement, so hacking or adding spyware through the manufacturer becomes the only halfway realistic method to get at the data. And that’s the the last two items become kind of important.

Out-of-Order problem

I realized I made a mistake in how I thought about time. Now there are many ways in which we as computer people have a wrong understanding of time, as Rethinking Time in Distributed Systems discusses(originally seen on EE380 Computer Systems Colloquium available via iTunes U, because I liked that lecture before everyone else thought it was cool) so this shouldn’t be entirely surprising. This is how I thought about timestamps:

Here we see the time in the leftmost column, think of it like Unix time. The number of the three columns to the right indicate the message IDs received at each server. The last three shows which message IDs the server would return if the user asked for messages after t=15. So far, so good.

Next, a message 35 showed up at t=16 and all three servers reflect this correctly. Still no problem.

Now we have a problem! Server 1 received a message with ID 17(I know message ID is 17 and t=17 but this was a coincidence and not intended, so there is no real connection between message ID and timestamp, in the example or in reality) and if anyone asks that particular server than all is well but the other two servers have no knowledge of this “message 17”. So they will respond to queries for “new” messages as if though server 1 hadn’t received anything. It’s not their fault, it’s server 1 that isn’t propagating this information as it should.

Now a new messag with ID 28 has shown up at server 2 and all three servers see this correctly, but message 17 still hasn’t registered at server 2 and 3! So when the user asks server 2 “Are there any new messages” they get an incomplete list and what is worse, now the user thinks it has all messages received up to and including t=18. Why would the user think this? It received information about message 28 and it was marked t=18.

Now finally the information about message 17 has propagated to servers 2 and 3. But this isn’t much help if the user asks for all messages received after t=18. Why would server 2 include this old message if the user asks for things strictly after t=18?

So this problem of out-of-order delivery means that using wall clock time to say “I only want new messages” isn’t viable. We’re at risk of losing messages and that’s a cardinal sin in any kind of messaging protocol.

Solving the out-of-order problem

So what is the solution? I have thought about many possible solutions.

- A constantly updating CRC checksum between the server and the client to catch aberrations? No, very unwieldy.

- How about looking at the acknowledged attribute of a message? No, that would mean we can’t support multiple clients and we shouldn’t paint ourselves into that corner.

- How about letting the server have a concept of a “thread of discussion” and let messages have a strict numerical ordering, kind of like in TCP? No, threads are client side things, we don’t want to tailor the server side stuff for that use case.

This is what I have concluded: we need the server to have a concept of a “client”, meaning a access point used by a user – as recognized by the system. Each client corresponds to a sequence of message IDs that have been fetched already. So when a client asks for “new” messages the server can look at all relevant message IDs, subtract any that have already been fetched and return the final assortment to the client.

So we distinguish between a message being acknowledged which means the recipient has told whoever they are talking to that they have the message and can’t refute that they have, and a message being fetched which means that a client has downloaded it. The former is something that two users are going to be interested in but the server doesn’t care. It uses a symmetric password to make sure clients are who they claim to be so there is little point in them checking the verification signature. Similarly a user cares little that “some clients” have downloaded a message from “the server”, even though this is highly relevant to both the server and the client.

This is true but I should also recognize that not having the server do more public key operations is a way to let the server handle more traffic. So even if I saw some benefit to verifying verification signatures on the server I probably wouldn’t because it would eat more CPU than it was worth.

Naïvely, the algorithm can be seen as this:

- Get all message IDs for the requesting user

- Get a list of all acknowledged message IDs for the requesting user

- Subtract the acknowledged message IDs from the list of all message IDs

- Return the final result

This is kind of pain though. Imagine if we hold messages for two weeks and we have several hundred thousands of messages? This would quickly end up being very inefficient. This means we now have to ask ourselves when we can stop worrying about the out-of-order problem.

In theory there is no upper limit to eventual consistency delays or replication lag or concurrency weirdness but in practice a messaging system with delays exceeding 30 seconds will not be fit for purpose. Users are going to be negatively affected. So if we set the upper limit to 5 minutes we’re not strictly speaking making sure we avoid all possible issues, but in practice we will encounter several other issues before the time=500 seconds limit becomes relevant. So I distinguish messages for a user as either being in the “consistent” block or the “inconsistent” block.

The inconsistent block is the last five minutes worth of messages. The consistent block is all the messages old than that. So we basically assume that the problem of out-of-order delivery as described above can only happen in this 5 minute period. Do we assume that all messages in the consistent block have been fetched? No, not at all. To figure out which messages are “new” to a client we can use the algorithm shown above if push comes to shove, but we will swiftly want to establish a “last known good” timestamp for a client.

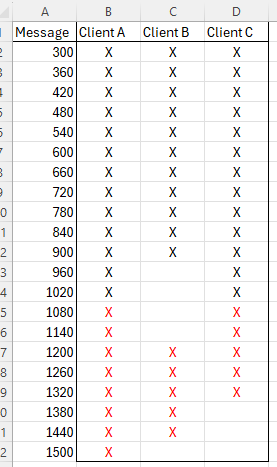

I’ll try to create a chart of that:

Here we imagine a message has arrived every 60 seconds and we see a list of which have been fetched by three different clients the user has. Here we establish a “last known good” value for client A as… time=1020

Why not 1500? Because the messages after 1020 are in the inconsistent range where we can’t rule out out-of-order delivery and have to go through the hassle of comparing the list of candidate message IDs to the list of fetched messages for client A, lest we miss one due to eventual consistency or whatever.

Client B? The last known good value is time=900. After time=900 we have the first unacknowledged message so henceforth we have to ask the backend “hey, give me all messages after time=900” and then check them against the list of fetched messages. Sure, there’s a bunch of messages recently that have been acknowledged but a request for “new” messages have to include the unfetched messages from earlier.

Client C is fairly simple, it hasn’t kept up with the absolute latest messages but the last known good value is still time=1020 just like client A.

So, for each client we would like a “last known good” value to make fetching new messages more efficient. If no such value exists yet we have to do the hard work involved in establishing this value as outlined above. In practice I don’t think “set A minus set B” where A and B are a few hundred thousand UUIDs is a terribly taxing operation for a computer to perform but it will be a very rare operation using the above decribed method. Once the LKG value is established we can fetch messages and there will only be a 5 minute overhead where we are meticulous to avoid out-of-order issues causing trouble.

We should limit how many clients are user can have. I think 5 is reasonable but making this value configurable to that the weird customer that wants 70 clients of one user for some reason can have that. I figure that the information about a client is miniscule, with just an LKG value really. The bulk of the data is the corresponding list of fetched messages which can range in the multiple of megabytes.

I am thinking about this as a ScyllaDB+Valkey setup where the LKG value is stored in Valkey(because it may be frequently updated but it can be derived from persistent data if Valkey has an aneurysm all of a sudden) and we can simply have the “fetched” table use “organization_id#user_id#client_id” as a partition key and add new entries every time the client fetches a message. I see no real need for a clustering key here since we are using this precisely because we don’t trust wall clock times.